In 1971, Zafrullah Chowdhury was a 30-year-old young man. He was studying FRCS in England when the Independence War broke out.

Jahanara Imam in her book 'Ekattorer Dinguli' writes that when the war broke out, Zafrullah Chowdhury skipped out on his FRCS exam and boarded a flight to Delhi to take part in the Independence War. He was accompanied by Dr. MA Mobin.

The Syrian Airlines flight they boarded was delayed for five hours in Damascus. Everyone got off the plane, but the two did not get off. Unbeknownst to them, a Pakistani colonel was waiting at the airport to detain the two 'absconding Pakistani citizens'. No one can be arrested inside a plane as it is an international zone, and so the two survived. The Pak colonel had to return disappointed.

After joining the war, he took part in guerilla warfare in the early stages. Later, along with surgeon Dr Mobin, he established the first field hospital at Melaghar for freedom fighters and refugees.

The temporary hospital with 480 beds was managed by five Bangladeshi doctors and a large number of female volunteers. None of the volunteers had any previous medical training.

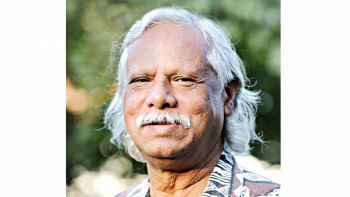

As the people's doctor passes away, he will surely continue to be remembered for his works, especially for his contribution to the country's health sector.

Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury held the position of chief advisor of the expert committee for Bangladesh national medicine policy in 1982. By implementing the recommendations of that committee, it was possible to increase the production of medicines locally and improve the quality of medicines, to eliminate harmful and unnecessary medicines, and to formulate policies regarding the price and import of medicines.

Seventeen hundred dangerous and unnecessary drugs were banned through the Essential Drugs Act. There was a lot of resistance at the time from foreign drug manufacturing companies, but the government eventually accepted the committee's advice. This policy became an example for many countries in the world in terms of market regulation of therapeutic drugs.

Zafrullah Chowdhury had started his work in the health sector of the country immediately after independence. He realised the sorry state of rural healthcare in the war-torn country. The Bangladesh Field Hospital of the Liberation War was converted into Gonoshasthaya Kendra on the last Sunday of 1972.

There is a beautiful story behind the naming of Gonoshasthaya Kendra involving Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

A concept paper titled 'Basic Health Care in Rural Area' was first presented in Dhaka in April 1972, which laid the theoretical foundation of the healthcare centre. This report became one of the foundations of subsequent international discussions on primary healthcare.

The then Bangladesh government objected to the name of the field hospital set to resume operations in the independent country. Frustrated, Zafrullah directly complained to Bangabandhu, "Mujib Bhai, they are not allowing us to build the field hospital."

Bangabandhu advised him to give a beautiful name to the hospital. After much discussion, Bangabandhu proposed that he would give three names, and Zafrullah would give three names. The best would be the name of the hospital. In the next meeting, Zafrullah started reading out names from his list. Number two was Gonoshasthaya Kendra. Bangabandhu stopped him and said, this name is beautiful. This will be the name of the hospital.

Bangabandhu did not stop only with helping with the name, he also allocated 23 acres of land for Gonoshasthaya Kendra. Several other individuals also donated a total of five acres of land from their family property for the Gonoshasthaya Kendra.

Through Gonoshasthaya Kendra, Zafrullah Chowdhury trained the less educated or uneducated rural people on vaccination and treatment of common diseases. These trained volunteers used to roam from village to village with the mantra of service to humanity. Village people used to get basic healthcare for mother and child, family planning advice etc from them.

Bangladesh Government's NGO web portal states that Gonoshasthaya Kendra's journey began with the motto 'Go to village, build village'. The volunteers of the Kendra would go to the village on their own initiative, live in the village, and taking the villagers with them would decide on the necessary programmes.

The functions of Gonoshasthaya Kendra can be roughly divided into two categories: direct services and indirect services. The first phase includes support to agriculture, community schools, primary health care centres and hospitals, technical training for women, nutrition development, disaster and relief management, etc. Gonoshasthaya Pharmaceuticals, Gonoshasthaya Intravenous Fluid Unit, Gonoshasthaya Basic Antibiotics Production Unit, Gonoshasthaya Printing etc. are some sources of income of Gonoshattha Kendras.

Gonoshasthaya Kendra was the first to introduce the concept of paramedics in Bangladesh. Then in 1977, Bangladesh government accepted it. Gonoshasthaya Kendra placed special emphasis on the training of paramedics and their own paramedics provide medical services to common people across the country. Thanks to these paramedics, the maternal and child mortality rates in the areas operated by them have decreased a lot, compared to the overall rate of the country.

Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury co-authored a research paper titled "Tubectomy by Paraprofessional Surgeons in Rural Bangladesh." On September 27, 1975, it was simultaneously published in the world-renowned medical journal Lancet from the United States and the United Kingdom. This was the first cover article published in the Lancet from the Indian subcontinent. During the rest of his life, many articles of Zafrullah were published in national and international journals. 'Research: A Method of Colonisation' published in 1977 was translated into Bangla, French, German, Italian, Dutch, Spanish, and many Indian languages.

Zafrullah Chowdhury started working as a project coordinator of Gonoshasthaya Kendra in 1972. He held that position for 37 years and retired from that position in May 2009.

The contribution of this great man did not go unnoticed or unappreciated.

In 1977, he received the highest civilian honour of the Bangladesh government, the Independence Award. In 1985, he was awarded the Ramon Magsaysay Award from the Philippines. In 1992, he received the Right Livelihood Award from Sweden. He also received the International Health Hero award of the University of Berkeley in the United States, and the Ahmed Sharif Memorial Award of Bangladesh.

Zafrullah Chowdhury was an optimistic person. Expressing his feelings after receiving the Ramon Magsaysay Award, he wrote: 'Where is the conscience of this world today? Where is our humanity? Is humanity asleep? No! People all over the world will rise again very soon against exploitation and imperialism, to end human misery.'

In 2023, Emeritus Professor Sirajul Islam Chowdhury described Dr. Zafrullah's overall contribution to Bangladesh as unique, and added that it is difficult to find another person like Zafrullah in contemporary society.

As a child, Zafrullah wanted to be a banker, but his mother encouraged him to become a doctor. In a speech he said, 'Now I can say, my mother showed me the right path.'

Zafrullah Chowdhury was born on 27 December 1941 in Raujan, in Chattogram district. His father was a student of revolutionary Masterda Surja Sen. Zafrullah passed matriculation from Nabakumar School, Bakshibazar, Dhaka and Intermediate from Dhaka College.

He passed MBBS with Distinction in Surgery from Dhaka Medical College in 1964. Then he studied FRCS from the Royal College of Surgeons, UK, from 1965 to 1971. Then when the war started, he left without taking the final exam. Later in 1990, he received an honorary FCGP from the College of General Practitioners. In May 2009, he was awarded a Doctor of Humanitarian Service by the World Organisation of Natural Medicine of Canada.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.